Introduction

Since the advent of MOOCs (massive, open, online courses), researchers, universities, companies and learning professionals have extensively studied their use and effectiveness. The popularity, access, economics and use of MOOCs, however, have evolved. Today, there is plenty of evidence that MOOCs provide the opportunity of bringing knowledge to students who may otherwise not have access to courses. In this article, I will explore the use of asynchronous MOOCs, those are, MOOCS that don’t involve a coordinated schedule of students with an instructor who facilitates.

It is estimated that as of 2020 there are over 16,000 MOOCs in existence, providing online learning to over 180 million students. The need for properly designed, effective and useful MOOCs has become important today more than ever due to the effects of a pandemic that has forced emergency transition to online delivery of courses. Self-paced, asynchronous courses should provide the necessary tools that make a course a complete and fulfilling learning experience in the absence of a live instructor and/or peers in a classroom. Some asynchronous online courses provide some level of support from an instructor who manages a course. Others are completely self-paced, where there is no scaffolding provided by a person. In the absence of human interaction, asynchronous MOOCs provide the means to verify knowledge acquisition, typically in the form of online exercises or questions, where feedback is automatically generated, based on the answer provided by the learner.

Even with a price tag on MOOCs, compared to the cost of higher education, in general MOOCS are quite affordable. However, with the monetization of MOOCs, some have evolved into being used as marketing tools to entice learners to enroll in additional for-pay certification programs, corporate training, colleges, or additional for-pay professional studies. Because of this evolution, it has become important to know how to evaluate MOOCS, and how to select MOOCs based on the specific needs of learners. As learning professionals, we should always look for ways of improving online, virtual or blended experiences for learners. Our instructional design processes for MOOCs must implement considerations and elements of evidence-based practices that result in high quality and effective learning. As learners, knowledge of how to evaluate MOOCs can help make good decisions when selecting MOOCs for our own professional development.

According to research, there are principles, evidence-based practices and approaches that can help learning professionals design and deliver quality online learning. In this Part 1 of my MOOCs series, I evaluate asynchronous MOOCs based on several established research-based teaching and learning principles. I present two examples of self-paced, asynchronous learning MOOCs, and critique their instructional design. In future articles I will delve into communities of inquiry, which provide a framework to evaluate blended, synchronous and virtual learning settings.

Definitions

What do I call a “MOOC”? We can create and deliver an entire course (or probably a curriculum) solely on the topic of approaches, definitions or application of each one of the letters in the MOOC acronym. To keep it simple, and for the purposes of my article, a MOOC is a massive open online course aimed at group participation and open online access. A MOOC has the following characteristics:

- MOOCs provide some form of interactivity where the learner can engage and actively participate (via communities, media, etc.) other than just reading.

- MOOCs are open to the general public (“massive” in this instance refers to availability and capacity to enroll and manage a relatively large number of people to a capacity that a classroom setting may not).

- MOOCs are completely online, whether synchronously or asynchronously delivered. A MOOC is delivered online in its entirety.

- Registration for a MOOC is open to the public (either free of charge or at a cost that is much less than the cost of the same course delivered by a university where the learner is located).

- MOOCs provide learning with specific objectives, a set of topics, clearly outlined.

What do I call a “BOOK”? I chose the word BOOK, not only because the word rhymes with MOOC, but also because in my experience I have encountered online courses that are nothing more than electronic versions of a book. Those are MOOCs that provide minimal or no interactivity, low level or no human support or scaffolding, and are minimally or not at all managed by a human being. Some MOOCs have been published online and left alone for whoever finds them. Just like a printed book, some BOOKs can have useful information, and even some form of contact information, but they have been published and either never updated (sometimes not even the technology required for them to render online is updated), or they have been published seemingly with the purpose of enticing learners to pursue additional certification programs or other for-pay professional development events. It is important to note, however, that the use of MOOCs as introductory courses for further certification programs or other types of professional development can be quite beneficial to the learners. A BOOK can serve a purpose and meet objectives. For example, a learner can use a BOOK to learn the basics on a topic and decide if its content or topic are of interest enough to advance further. However, under certain circumstances, learners can become frustrated when a MOOC is misleading in its description, when a MOOC doesn’t provide the means for obtaining responses when questions arise, or in instances when the MOOC content or the technology used for publishing it are outdated. In summary, a “BOOK” is a MOOC that is ineffective because it does not provide an adequate, satisfactory learning experience, or its instructional design doesn’t conform with evidence-based practices for effective asynchronous online learning.

The Examples

I selected two MOOCs from Carnegie Mellon University’s Open Learning Initiative as examples of a MOOC and a BOOK. The first MOOC is a free course entitled “Evidence-Based Management”. According to the course description, it “…strengthens your EBM skills and critical mindset to improve the quality of your decisions”. The course is authored by the Center for Evidence Based Management, an organization based in the Netherlands that claims to be “the leading authority on evidence-based practice in the field of management and leadership”.

The second MOOC is a paid course, also from Carnegie Mellon University’s Open Learning Initiative. The title of the course is “Elementary French I — Independent Paid”. According to the course description, it “…is a carefully sequenced and highly interactive presentation of French language and culture in a media-rich course environment. The latest update includes a self-paced version of the course with scored assessments for independent learners, and new video shot in France and Québec with young professional actors. It is designed to be used as a full course of study.”. This course is the self-paced version of the “Elementary French I”, which is the version of the course with videoconferencing and the presence of an instructor. The instructor-assisted version is more expensive and it’s not fully asynchronous.

The Design Principles

In Part 1 of this case study, my critique is based on Chickering-Gamson’s Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education, which provide a good framework for instructional design and learning delivery that is based on good teaching and learning practices. The seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education that Chickering-Gamson identify in their research can serve as guidelines for anyone involved in learning, instructional design and/or learning technology. The principles also transcend programs, subject matter, and characteristics or identities of learners. Furthermore, these principles align with the assumptions of andragogy or principles of adult learning, which makes them applicable to adult education in settings other than higher education. The Chickering-Gamson principles are:

- 1. Encourages contact between students and faculty.

- 2. Develops reciprocity and cooperation among students.

- 3. Encourages active learning.

- 4. Gives prompt feedback.

- 5. Emphasizes time on task.

- 6. Communicates high expectations.

- 7. Respects diverse talents and ways of learning.

In Parts 2 and 3 of this case study, I delve into evaluating MOOCs using Mayer’s Design Principles for Multimedia Design and Universal Design for Learning. What follows is an evaluation of the first MOOC from the lens of the above-mentioned principles.

MOOC 1: Evidence-Based Management Course

Principle 1: Encourages contact between students and faculty. This principle emphasizes the importance of student-faculty contact in student motivation and involvement. Such relationship enhances students’ intellectual commitment and encourages them to think about their own values and future plans.

The course completely fails to encourage any type of contact between the students and faculty (or maybe the company?) that designed and published this course. This course lacks any type of online contact information or any means of communication between any of its authors and/or any of the students, unless the student is located in a part of the world where they can afford to make a call to the Netherlands.

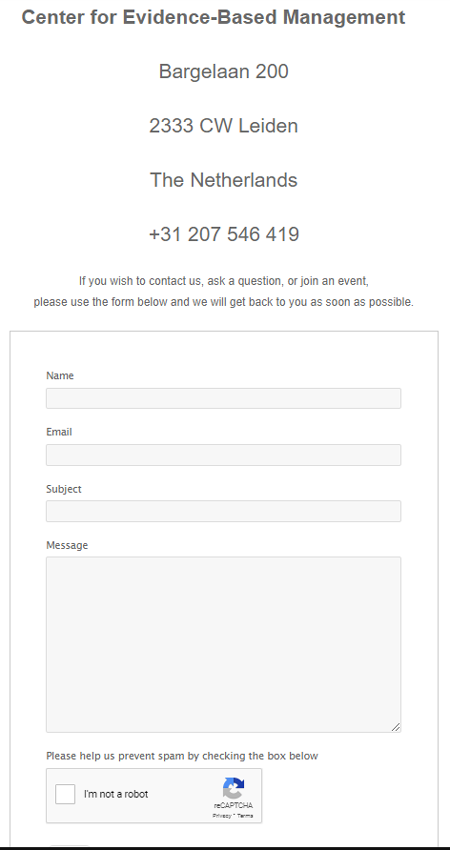

The introductory description of the course contains a link that says: “The full certification course can be found here”, where it takes the learner to a page to contact that organization (shown on the right). However, even that contact page lacks “human touch” in the sense that it’s just a form page with no design whatsoever. Because of the lack of any type of online communication or interaction between the students and the instructors, this course misses an opportunity of engaging learners who are interested in the subject.

Principle 2: Develops Reciprocity and Cooperation Among Students. This principle emphasizes collaboration and interaction among learners and the instructor. Learning, like good work, is collaborative and social, not competitive and isolated. Sharing one’s own ideas and responding to others’ reactions sharpens thinking and deepens understanding.

Asynchronous online courses can promote collaboration and interaction among students by establishing communities using several online tools, such as forums, chats, or group projects. In online learning, this type of collaboration and interaction with other students is quite useful. In addition to not providing reliable contact between the instructor and the students, this MOOC doesn’t provide any means for other students to collaborate. That means that students who take the course are isolated and cannot form any community where they can provide mutual support.

The Center for Evidence-Based Management, the author of this MOOC, has a website and a LinkedIn page. Professionals who are interested in this topic can join that organization as paid members, where they can have access to an online community forum. Their LinkedIn page only presents information leading to their main website; it is not a LinkedIn group. That means that students interested in any kind of collaboration or belonging to a community of this subject matter can only do so by joining that organization and becoming paid members. As a learning event, however, this particular course completely fails in providing any means for collaboration, group activities, or communication among students with interest in this course. At best, it requires joining the organization that authored the course in order to reach other members.

Principle 3: Encourages active learning. This principle addresses interactivity in the different learning activities of the MOOC. It is expected that learners actively participate in several interactive exercises throughout the course in order to reinforce and apply or integrate their learning into their lives.

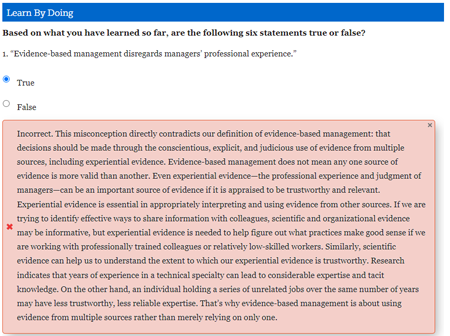

According to Chickering-Gamson, “Learning is not a spectator sport”. Not much learning can happen by rote reading or having no availability for interaction between the subject matter experts and the students. Although this course provides several reflection and application activities, all of them involve only reading, selecting answers and typing text. The feedback obtained is automatic and linear, without the opportunity of actively participating in the class or asking additional questions.

The image above shows an example of one of their “Learn by Doing” activities. The activity consists of a set of simple true/false questions with feedback based on the correct or incorrect answer selection. The provided feedback is extensive and very detailed; however, it only consists of text detailing the reason for the selected answer being correct or incorrect. Furthermore, the content does not encourage further exploration, nor does it provide other resources to research (aside from the references and links to the organization’s certification program). Additionally, there is no human being to consult should a student has further questions or if the provided feedback is not sufficient to clarify or answer questions.

Principle 4: Gives prompt feedback. This principle addresses the need for students help with assessing existing knowledge and competence. Students need frequent opportunities to perform and receive suggestions for improvement at various points during the course, as well as opportunities to reflect on what they have learned.

Engagement and feedback go hand-by-hand. That is particularly true for first-time learners using a MOOC. Chickering-Gamson states that "students need help in assessing existing knowledge and competence", especially in the beginning of a course. Throughout this MOOC, the only feedback available is through their "Learn by Doing" assessment questions, and through additional similar questions at the end of each section. The session-end questions are under a "Did I Get This" subtitle. However, after going through the introductory section, "What Is Evidence-Based Management?", it was quite frustrating providing the correct answer and consequently the right feedback.

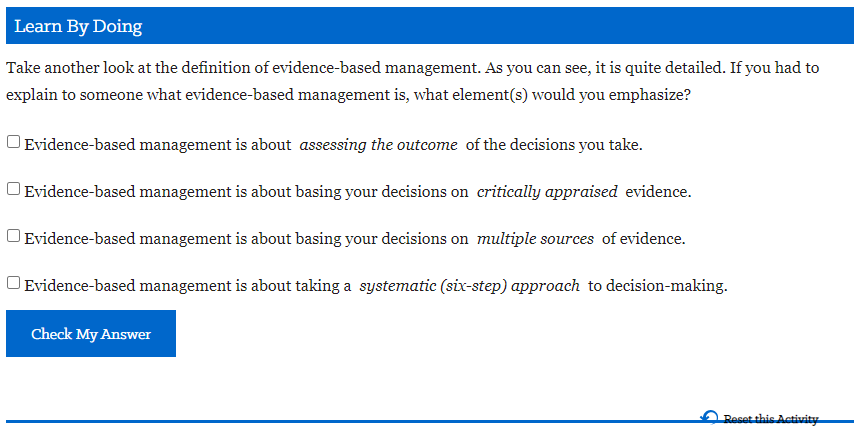

Below is a screenshot of the first "Learning By Doing" activity of the MOOC. In this question, there isn’t any signifier implying that there can be more than one correct answer. I figured that I can choose more than one answer because my experience in eLearning development tells me that checkboxes typically mean more than one choice, as opposed to radio boxes which mean that the question allows only one choice.

In terms of providing feedback, when selecting a wrong choice(s) the MOOC does provide a message with feedback about why that is a wrong choice. However, there are 64 possible combinations of choices that I can make to obtain the correct answer. The image below shows the feedback provided when I selected only the first choice.

This MOOC also provides some reflection questions. Reflection questions are an excellent way for learners to look back over what or how they have learned. Though reflection questions can be an isolated event where learners use their metacognition to reflect, a reflection can also be used for scaffolding by the instructor. An example of a reflection question at the end of a section of this MOOC is shown below.

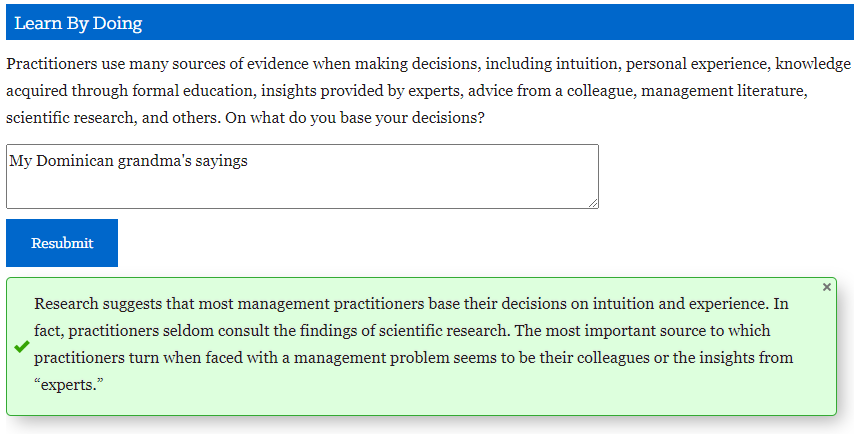

As you can see, the answer that I provided is completely unrelated to the subject matter, and obviously not “evidence-based”, yet, the feedback is exactly the same regardless of the type of answer that I provide. Without any scaffolding or any way of connecting with faculty or other students, there’s no way to know if my reflections and assessments are valuable.

Principle 5: Emphasizes time on task. Text for principle 5.

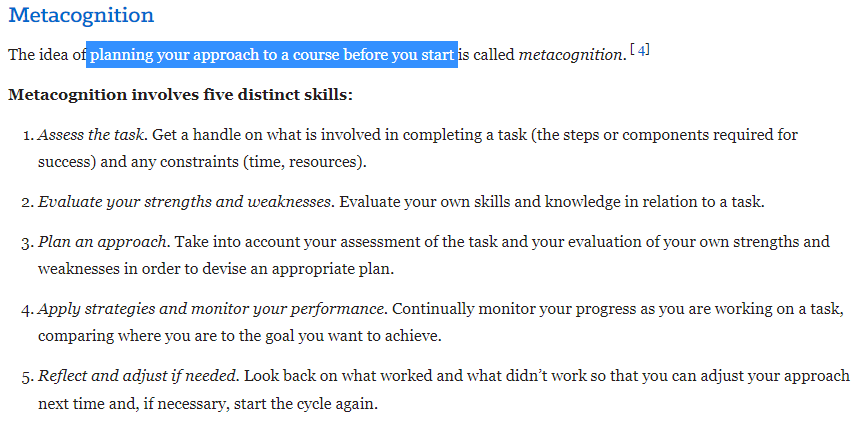

Principle 6: Communicates high expectations. A good effort was made by the Instructional Designers of this MOOC in setting appropriate student expectations for the learning experience. The introductory sections of the course contains information and recommendations on how to complete the course successfully. It details the use of metacognition to plan the student's approach to the course before starting. Below is a screenshot of the information on metacognition.

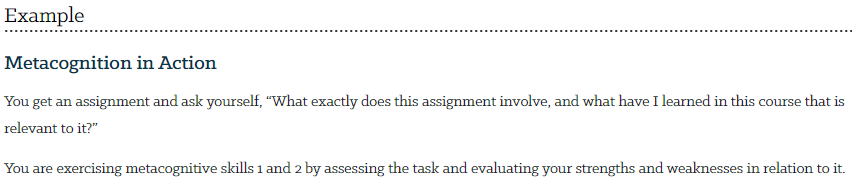

To provide additional support on how to successfully plan and take the course, this section of the course also provides specific examples on how to apply the outlined metacognition skills. Below is a screenshot of part of one of the additional examples on how to apply metacognition.

By providing the means to properly plan and apply the necessary skills and knowledge required to successfully take the course, this MOOC demonstrates a way of communicating high expectations from the student. However, this poses an interesting dilemma. On one hand, the MOOC clearly states the expectations for the course, on the other hand this communication is letting the student know that they are responsible for doing all the work, on their own and without any additional support (other than the contact form).

Principle 7: Respects diverse talents and ways of learning. This principle addresses the fact that students need the opportunity to show their talents and learn in ways that work for them, where they can bring their different talents and preferences for learning. Also, as good practice, learners can be enticed to learning in new ways that do not come so easily.

Learners differ widely in their capacity to navigate their physical environment. As per this principle, and also in alignment with UDL guidelines, the course must provide alternative means for response, selection, and composition. Those can be provided by many different ways, and considering that MOOCs are open to the general public, the provision for such alternatives should be wide.

Some of the most common forms of varied media are text, speech, drawings, illustrations, music/sound and video. This course is limited to text and illustrations. The screenshot of one of its pages shown here is typical throughout the entire course. There is no video and no audio of any kind. Consequently, this course fails to provide alternative media for diverse ways of learning.

Learners can use social media to show their talents by connecting, communicating, collaborating and increasing or improving their range of expression as they learn. The lack of variety in the media used in the course severely limits learners from a wider range of communication and expression. According to research, a variety of means for expression also increase the variety of problem-solving strategies. An evidence-based management course like this one can become a much richer learning experience by adding multiple media, along with the means for establishing a community of practice.

My Recommendations

To make this MOOC better, I recommend:

- Use multimedia, videos, narrations and audio.

- Use social media to create a community where collaborative learning can occur.

- Provide mentoring, scaffolding, or a point of contact from an experienced professional in the subject matter.

- Add case studies and assign projects.

References

- Means, Barbara, Marianne Bakia and Robert Murphy (2014). "Online and Blended Learning in Higher Education". Learning Online: What Research Tells Us About Whether, When and How. New York, Routledge: 40-70.

- LeBlanc, P. (2021, July 6). What 2U’s $800 Million Deal To Acquire EdX Means For Higher Ed. Forbes.

- Job, D & Fatimayin, Foluke. (2015). Andragogical Theory in Open and Distance Learning: How Relevant for Noun Students. 3. 204.

- Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P. et al. Online University Teaching During and After the Covid-19 Crisis: Refocusing Teacher Presence and Learning Activity. Postdigit Sci Educ 2, 923–945 (2020).

- Chickering, Arthur & Gamson, Zelda. (2006). Seven Principles of Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 1991. 63 - 69. 10.1002/tl.37219914708.

- Anne Hartree (1984) Malcolm Knowles’ Theory of Andragogy: A Critique, International Journal of Lifelong Education, 3:3, 203-210, DOI: 10.1080/0260137840030304

- Mayer, R. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (2nd ed., Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139547369