On March 26th, 1997, the police discovered the bodies of 39 people in Rancho Santa Fe, CA. The bodies were of members of Heaven's Gate, a UFO religious group. They had partaken in a coordinated series of ritual suicides, with the intention of reaching an extraterrestrial spacecraft following a comet. It was later discovered that all the males in the group had been castrated.

At first look, we can only wonder why people would submit themselves to voluntary mutilation and suicide. However, there is abundant research on the negative influence that high-demand, controlling groups (also known as cults) impose on group members' critical thinking (Chambers, Langone, Dole and Grice, 1994), leading them to actions that they otherwise would never take on their own. In this article, I explore and compare the positive influence in critical thinking promoted by ethical education with the negative influence exercised by a cult leader (or leadership) – the “anti-teacher” – under the lens of complex cognition. I’ll start with terminology and definitions.

Influence is the capacity to have an effect on the character, development, or behavior of someone or something, or the effect itself. Through the lifespan of every human being, influence is ubiquitous; it is in the words we use, in the things we see, in the music we listen, and in everything that we contact or communicate with (Dubrow-Marshall, 2010). We are influencers as much as we are influenced. Our cultures, upbringing, schooling, relationships and past times always exercise a degree of influence in our ways of living and thinking, and in the decisions that we make.

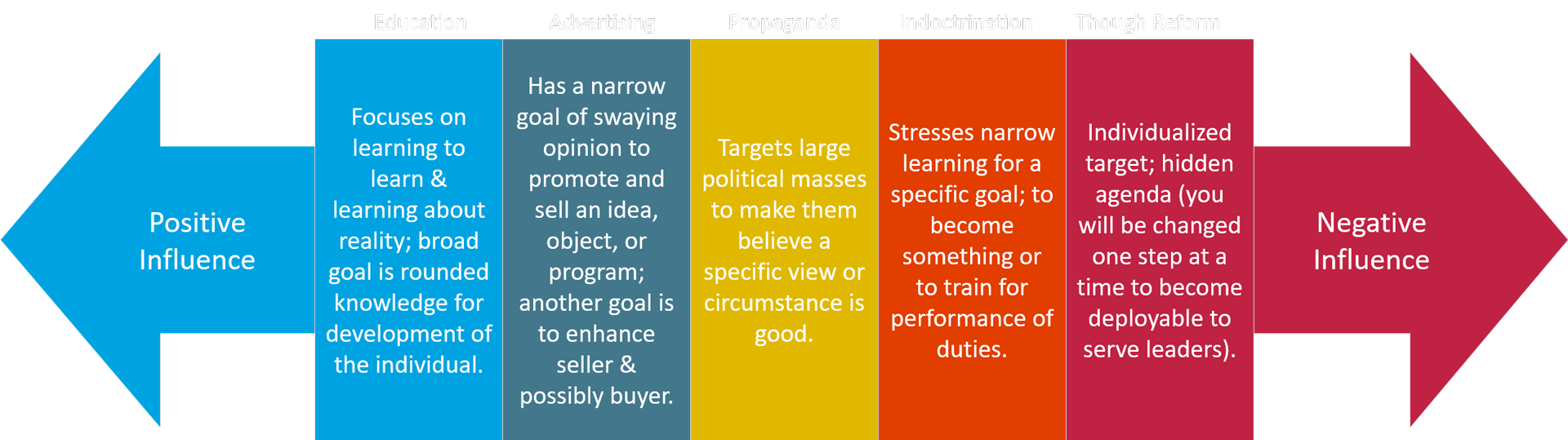

Experts in the matter of influence established an influence continuum that ranges from highly beneficial to extremely harmful. The diagram below shows the portion of the “Continuum of Influence and Persuasion” chart (Singer, 1995), demonstrating the influence range for the Breadth of Learning category. The impact of a given influential effect on people can range from extremely beneficial (labeled in the diagram as education), to unethical, morally questionable, and even deadly (labeled in the diagram as thought reform, Dubrow-Marshall, 2010).

Continuum of Influence and Persuasion - Breadth of Learning

In traditional behavioralist approaches to learning, it’s expected that the teacher influences the students. The teacher-learner relationship is critical in shaping learners’ behaviors as well as social and academic development since the role of the teacher is to manipulate the environment to shape behavior. Other approaches to learning, such as constructivism, emphasize the collaborative nature of learning, which encourage mutual influence from and to all participants in the learning event, including the teacher (Bransford, et al., 2000). Learners’ interactions with teachers and peers, along with the way the teacher manages interpersonal interactions, influence the social, emotional and academic development of the student (Chen et al., 2020). Beneficial or positive influence in learning, then, is the type of influence that encourages and stimulates the learner’s behaviors that can enhance the learner’s functioning and resilience to difficulties and encourages students to acquire strategic metacognitive knowledge to improve their learning. The teacher implements learning strategies that include reflection and questioning strategies, strategies that also encourage critical thinking, problem solving and self-regulatory behavior (Hartman, 2001).

Negative influence in learning is, by contrast, a teacher-student relationship that shapes the students towards a specific, pre-determined behavior or belief, disregarding the learner’s academic or social development. The anti-teacher discourages critical thinking, and behavior is regulated in alignment with a specific agenda by the teacher. The power dynamic between the influencer and the influenced becomes noticeably more pronounced. The anti-teacher also discourages any further reflection or questioning, in fact, reflection and questioning can be punishable. In a way, negative influence can be seen as a misleading advanced organizer (Ausubel, 1963), one that prepares the learner's conceptual anchoring and obliterative subsumption under objectives that are different than the ones presumed by (or told to) the learner. It can also be perceived as misrepresentation of ideas using faulty logic. Though there is no evidence that critical thinking can be completely suppressed from a learner, it can be influenced (Galanter, 1989).

In constructivist approaches to learning, the quality of knowledge varies from person to person, and it's also influenced by the world around them (Martinez, 2010). Truth is a construct, which it's expected to improve over time. In ethical education, we use constructivist approaches, positive reinforcement and scaffolding to encourage learning. In high-demand, controlling groups, such as cults, ideas and knowledge are misrepresented as absolutes, therefore, no further questioning, research or exploration is expected. Instead of deepening insight that is conducive to better understanding, the anti-teacher hinders or precludes learners’ critical thinking from advancing.

Critical thinking is one of the four subdivisions of metacognition that Martinez (Martinez, 2010) states under the subject of Complex Cognition: "Critical thinking is the evaluation of ideas for their quality, especially in judging whether they make sense". When learners make use of their critical thinking, they pursue understanding by applying, analyzing, interpreting, contextualizing and synthetizing multiple data sources and perspectives (Heick, 2019). In teaching, there are many strategies to encourage or facilitate the cognitive act of thinking critically. Some strategies for critical thinking are:

- 1. Challenge all assumptions

- 2. Suspend judgement

- 3. Revise conclusions based on new evidence

- 4. Emphasize data over beliefs

- 5. Ongoing test ideas

- 6. Support the perspective that mistakes are data

- 7. Consider possibilities and ideas without (always) accepting them

- 8. Look for what others have missed

One important aspect of critical thinking is sensemaking. Critical thinking is driven by the question "What is true?". It's also driven by finding meaning of facts and ideas. In ethical education, the teacher can provide insights by stimulating the coherence of knowledge; stories, ideas and facts are presented as consistent to learners, and learners are encouraged to explore and test them by themselves. On the other hand, in a cultic setting, though ideas and facts are presented cohesively, the lack of consistency of the information or the lack of data to support claims are distorted, misleading, false or forcibly ignored. The cult leadership uses psychological tools or tactics to pressure the learner to accept what they are told as absolute facts and truths. Cialdini (Caldini, 1985) organized the most common tactics found in his studies of the processes whereby people are persuaded and reach their decisions. He refers to people or institutions imparting negative influence as “persuaders” or “compliance practitioners”. He enumerates six fundamental social and psychological principles underlying the tactics used by them:

- 1. Rule of Reciprocity - The decision to comply with another's request is frequently influenced by the reciprocity rule. One favorite and profitable tactic of certain compliance professionals is to give something to another before asking for a return favor.

- 2. Commitment and Consistency - Many compliance professionals try to induce people to take an initial position that is consistent with a behavior they will later request from these people. Commitments are most effective when they are active, public, effortful, and viewed as internally motivated (uncoerced).

- 3. Social Proof - Social proof is most influential under two conditions:

- (a) uncertainty (when people are unsure, when the situation is ambiguous, they are more likely to attend to the actions of others and to accept those actions as correct), and

- (b) similarity (people are more inclined to follow the lead of similar others).

- 4. Liking - People prefer to say yes to individuals they know and like. Compliance professionals increase their overall attractiveness and their consequent effectiveness.

- 5. Authority - Deference to authorities can occur in a mindless fashion as a kind of decision-making shortcut and in response to the mere symbols of authority rather than to its substance.

- 6. Scarcity - People assign more value to opportunities when they are less available. As things become less accessible, we lose freedoms. According to psychological reactance theory, we respond to the loss of freedoms by wanting to have them more than before. Research indicates that the act of limiting access to a message causes individuals to want to receive it more and to become more favorable to it.

When calibrating knowledge quality, correspondence is another factor to consider. Correspondence is related to the data that supports or clarifies the claims about facts and ideas. It refers to the direct information that proves claims to be true. In ethical education, the teacher provides scaffolding and a wealth of supporting resources; trust in the teacher is built during the teaching process, creativity is encouraged, and testing of and detachment from the data are also present. In cultic groups, however, the anti-teacher uses any combination of isolation or coercion tactics to replace creativity with negative critique, trust in the teacher is forced upon the members of the group, and fulfillment and connection with the group supersede testing and detachment from data.

In learning, cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) is a means to facilitate the cognitive processes of accommodation and assimilation, which are central to knowledge development. In psychology, cognitive dissonance is described as an uncomfortable internal state occurring when new information conflicts with commonly held beliefs. When describing cognitive dissonance theory, Martinez (2010) poses an example where a student states "I don't like science". For the purposes of demonstrating cognitive dissonance, he then proceeds to ask what can happen when the student later finds him/herself enjoying participating in a science project, demonstrating dissonance in the form of the clash between what the student experiences (joy) and the belief stated (dislike for science). In this instance the expression of dislike might come from a place where the student expresses doubt about understanding, hence the hesitation. Therefore, the strategy for motivating the learner used by the ethical teacher involves supporting the student in modifying the belief to match what (s)he experiences (or does). The teacher can encourage the student to revisit her/his beliefs and conclusions about them (Martinez, 2010).

The anti-teacher, on the other hand, attempts to quell cognitive dissonance by psychologically conditioning the students’ use of their cognitive abilities (Nishida & Kuroda, 2004). There are many ways used by a cult leader or leadership to maintain followers in alignment with their imposed belief, attitudes or actions. One of the most common strategies to hinder cognitive dissonance is what Lifton (1961) lists in his “Eight Criteria for Thought Reform” as “loading the language”, where in a cultic setting, it is expected that the group interprets or uses words and phrases in new ways so that often the outside world does not understand. Part of this jargon consists of what Lifton characterizes as “thought-terminating clichés”, which are (cult-)specific terms that serve to alter members’ thought processes to conform to the group's way of thinking. When exposed to new information that conflicts with their currently imposed and held beliefs and attitudes, the student’s internal state makes him/her dismiss the new idea or end the conversation with clichés and platitudes to justify their actions or beliefs. Examples of thought-terminating clichés are:

- “Everything happens for a reason.”

- “Why? Because I said so.”

- “I’m the parent, that’s why!”

- “It's a matter of opinion.”

- “We will have to agree to disagree.”

It is important to note that using expressions like the above-listed does not make a person a member of a high-demand, controlling group. It is rather the misuse and abuse of such expressions with the intent of avoiding the use of cognitive dissonance to learn, grow and/or change a given course of action.

The effects of the negative influence of high-demand, controlling groups from a complex cognition perspective helps explains voluntary participation in events like the one presented in my introduction. As individuals, as parents or as members of our communities, we should make efforts to ensure that the information and education that we and our loved ones receive is reliable, and allows us our freedom to think, interpret, conclude, choose and explore.

There is plenty more information about harmful groups or people who aim at negatively influencing others for their own personal gain. Anyone interested in additional information about such groups or people can access the resources of the place where I found research on those groups.

References

- Ausubel, D. P. The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning. New York: Gruene and Stratton, 1963

- Bransford, John D., Ann L. Brown, and Rodney R. Cocking. How people learn. Vol. 11. Washington, DC: National academy press, 2000.

- Chambers, W., Langone, M. D., Dole, A., & Grice, J. (1994). Group Psychological Abuse Scale: A measure of cultic behavior. Cultic Studies Journal, 11(1), 88-117.

- Cialdini, R.B. (1985). Influence. Science and Practice, Foresman and Company.

- Chen Jing, Jiang Hui, Justice Laura M., Lin Tzu-Jung, Purtell Kelly M., Ansari Arya (2020). Influences of Teacher–Child Relationships and Classroom Social Management on Child-Perceived Peer Social Experiences During Early School Years. Frontiers in Psychology. 11, 2746. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586991

- Dubrow-Marshall, Ph.D. The Influence Continuum—the Good, the Dubious, and the Harmful—Evidence and Implications for Policy and Practice in the 21st Century. International Journal of Cultic Studies Vol. 1, 2010, 1-12.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, Ill: Row, Peterson.

- Galanter, M. (1989). Cults: Faith, healing, and coercion. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hartman, H.J. (2001). Metacognition in Learning and Instruction : Theory, Research and Practice. Springer Netherlands.

- Heick, Terry. teachthought (2019). https://www.teachthought.com/critical-thinking/critical-thinking/, Accessed 22 December 2021.

- Lifton, R. J. (1961). Thought reform and the psychology of totalism: A study of "brainwashing" in China. Norton.

- Lifton, R. J. (1989). Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of Brainwashing in China. UNC Press. p. 429.

- Martinez, M. E. (2010). Complex cognition. In Learning and Cognition: The Design of the Mind (pp. 95-77, 119–152).

- Morvan, Camille, and Alexander O'Connor (2017). An Analysis of Leon Festinger's a Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Macat International Limited.

- Nishida, K., & Kuroda, F. (2004). The influence of life in “destructive cults” on ex-cultist’s psychological problems, after leaving the cults. Japanese Journal of Psychology, 75(1), 9-15. (Original publication is in Japanese, but an English translation is accessible here.)

- Singer, M. T., Lalich, J., & Lifton, R. J. (1995). Cults in Our Midst.